The stereoscopic still image pairs embedded on this page are formatted for cross-eye free-viewing.

As we have come to understand, stereoscopic vision is enabled by the lateral positioning of the two eyes. The “binocular disparity” created by lateral parallax offset in the images presented to the left and right eye allows a fusion of the two images in the visual cortex to create a sense of depth termed stereopsis.

It is possible to present other disparities to the two eyes such as those of hue, luminance, and contour, that can result in the phenomenon known as “binocular rivalry“. In the early years after its discovery, this phenomenon was termed “retinal rivalry” in recognition of the fact that the two retinae were the source of the discordant binocular input. During the last century, that term was supplanted by “binocular rivalry” in the scientific research community. I first learned of the effect as “retinal rivalry” via the stereoscopic community (which typically uses that older term), thus I tend to use the two terms interchangeably. Stereopsis represents a form of interocular cooperation, while binocular rivalry involves a form of competition between stimuli presented to the two eyes. However it is possible for the two modes to coexist in the perception of an image as we can see in the image below.

.

.

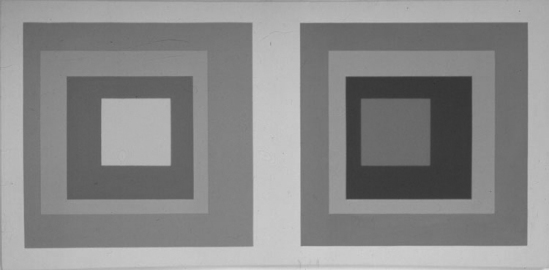

Roger Ferragallo has a long history of creating stereoscopic work. This stereoscopic painting from 1972, “Homage to Albers,” is an elegant study in the use of binocular parallax disparity coupled with binocular rivalry to create both a sense of depth and an effect termed luster. When fusing the left and right images through free viewing (or other means of viewing stereoscopic image pairs) one has the sense of experiencing hitherto unseen colors of shimmering luster seen floating at differing levels of space. The particular form of binocular rivalry Ferragallo employed in this work is referred to as color rivalry.

Converting the image to greyscale reveals that in his painting Ferragallo also employed the properties of a subtle luminance rivalry in concert with that of the color’s hue and saturation.

Ferragallo’s writing on this painting and his other work is available on his flash based website. Following are his notes on “Homage to Albers” (I have added hyperlinks):

“In dedicating this painting to Albers, I was mindful of many beautiful color harmonies in his series of paintings called ‘Homage to the Square’. What I have done in this painting is to shift the position of the squares in a stereo construction (disparity) so that the squares themselves appear to be situated free of the canvas. It was also my intention to explore the possibilities of the binocular optical mixture (in the mind) of colors and, indeed, I did find that optical mixture of colors does occur (in freevision fusion). Experimenting with a great many colored papers, I have observed that by binocular fusion one can obtain sublety in color mixtures as well as the vibrancy of luster (atmospheric effects). In (this) painting the large green square combines with its turquoise mate to produce a softly vibrant blue-green field. This effect is caused by our optically mixing two different hues of similar value. Suspended over this blue-green field is a square plate having a strong blue tint that hovers above as the nearest figure in space. The inner blue-violet square mates with a red of approximately the same value. This combination produces a very lustrous red-violet that acts as a window below the blue plate mentioned above. It gives this hovering blue plate the illusion that it is (in atmosphere) transparent. Sunk deep in this red-violet is the smaller red-orange and yellow square that appears to penetrate below the level of the canvas and they fuse to produce a glowing yellow-orange. The whole painting, with its two inner warm-color squares surrounded by the cooler field, seems to give the feeling of an interior room that is being (suffused atmospherically with light) illuminated.”

.

.

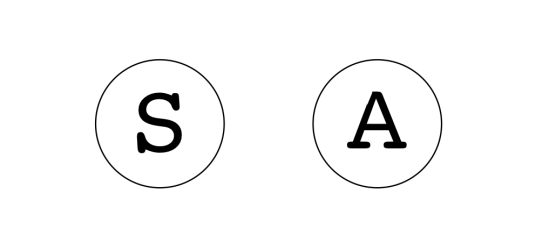

Giambattista della Porta has been credited as the first to describe retinal rivalry in 1593. In 1838 the inventor of the stereoscope, Charles Wheatstone, placed the image pair shown above into a stereoscope to demonstrate how disparities of contour create ambiguous perception:

“If a and b [shown as S and A in the drawing above] are each presented at the same time to a different eye, the common border will remain constant, while the letter within it will change alternately from that which would be perceived by the right eye alone to that which would be perceived by the left eye alone. At the moment of change the letter which has just been seen breaks into fragments, while fragments of the letter which is about to appear mingle with them, and are immediately after replaced by the entire letter. It does not appear to be in the power of the will to determine the appearance of either of the letters, but the duration of the appearance seems to depend on causes which are under our control: thus if the two pictures be equally illuminated, the alternations appear in general of equal duration; but if one picture be more illuminated than the other, that which is less so will be perceived during a shorter time.”

Wheatstone’s discovery stimulated a fresh wave of interest in studying the implications that this mode of perception raised. Hermann von Helmholtz, William James, and other imminent researchers worked to develop rational theories to explain the phenomenon of binocular rivalry. During the last century, empirical research on binocular rivalry contributed the first important insights into the neuronal mechanisms of subjective visual perception. Binocular rivalry continues to serve as a tool for for exploring the neural concomitants of conscious visual awareness and perceptual organization. Many visual artists have leveraged to power of binocular rivalry in their work, particularly in concert with the power of stereopsis.

.

.

Salvador Dalí had a lifelong interest in stereoscopic perception, however it was not until the 1970’s that he began producing a series of stereoscopic paintings (18 stereoscopic paintings and studies –some unfinished– are listed in his output from that era) In “Battle in the Clouds” (1974) he employed binocular rivalry in the color used on both sides of a horizon line. The wall as a blue sky with battle scene in the panel on the right (in this cross-eye view) and the pink color gradient on the left create a strong rivalry. The white halation around the left image of the seated Gala adds a binocular rivalry luster as she appears to float in front of the picture plane. The hallway set in the wall/sky is painted with a strong parallax that creates a deep opening leading to the distant moon.

.

.

Dalí incorporates binocular rivalry in this pair of stereoscopic paintings comprising the unfinished work,“Dalí from the Back Painting Gala from the Back Eternalized by Six Virtual Corneas Provisionally Reflected in Six Real Mirrors” (1977). Note the colors of the drapes and of Dalí’s shirt are swapped in the left and right paintings. This provides a lustrous sheen reminiscent of silk or velvet. There are other variations as well on the canvas, the walls, mirror frame, and of course that of the unpainted faces in the right image (appearing on the left in this pair as they are swapped for cross-eye free-viewing).

.

.

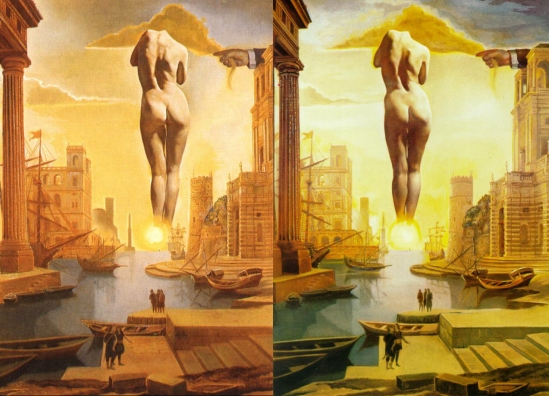

“Dalí’s Hand Drawing Back the Golden Fleece in the Form of a Cloud to Show Gala the Dawn, Completely Nude, Very, Very Far Away Behind the Sun” (1977) makes use of very subtle binocular rivalry to create a luminous space.

“Dalí’s Hand Drawing Back the Golden Fleece in the Form of a Cloud to Show Gala the Dawn, Completely Nude, Very, Very Far Away Behind the Sun” (1977) makes use of very subtle binocular rivalry to create a luminous space.

.

.

In this stereoscopic photo I am squatting down to view the pair of paintings constituting, “Athens Is Burning! The School of Athens and the Fire in the Borgo” (1979-1980) through a floor level modification of a Wheatstone mirror viewer in the Dalí Theatre-Museum in Figueres. I have visited the museum several times and had never thought to reveal the structure of the mirror viewer in the way that Edmund Fung did in this movie available on his Flickr.

.

.

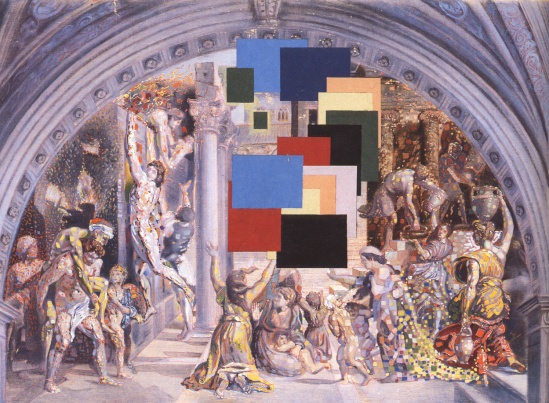

In “Athens Is Burning! The School of Athens and the Fire in the Borgo” (1979-1980), Dalí incorporated both simple stereoscopic rendering with the floating rectangles and extreme binocular rivalry with his modified versions of the Raphael paintings “The School of Athens” (1509-1510) and “The Fire in the Borgo”(1514). The binocular rivalry makes it difficult to free view as the eye is continuously drawn across the scene in an attempt to fixate upon disparate points thus breaking the stereoscopic fusion created by the floating rectangles.

.

.

Click on the image above to view a larger copy of one of the stereo pairs of “Athens Is Burning! The School of Athens and the Fire in the Borgo”. The larger image reveals much of the detail missing in the much smaller pairs shown in the previous panel, thus providing some sense of the complexity missing from the smaller images. I created the side-by-side panel of the stereoscopic pair from separate left and right images that I downloaded from the web, corrected for geometric distortions (introduced by the angle at which the photos were shot), and vertical alignment. Having access to larger images for making into a side-by-side cross-eye stereo pair for free viewing would have produced superior results.

.

.

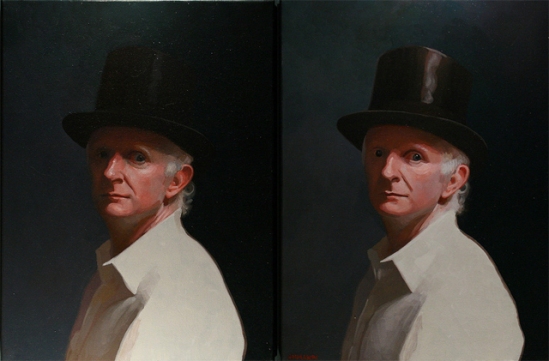

Alan Ammann employed subtle binocular rivalry by enhancing the specular reflection on one image of the top hat to create a lustrous silken sheen in his hand painted 3D portrait of Andrew Leibs (2009).

.

.

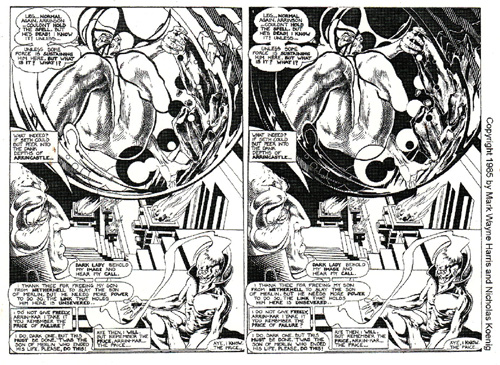

Ray Zone gives a brief history of binocular rivalry (retinal rivalry) on his web page “Glimmerings” and writes of his decision to incorporate the technique in his 2D to 3D conversion of the comic book page shown above:

“When I discovered the binocular experiments of Wells, Jastrow and Lindblom, I resolved to use retinal rivalry in some of my 3-D comics work. I found a perfect opportunity in 1985 with the Merlin Realm In 3-D comic book issued by Blackthorne Publishing. Converting the art by Nicholas Koenig to 3-D for page 23 of the magical tale, I juxtaposed black and white elements within an imprisoning mystic globe encircling a magician. Here, I felt, was a perfect image for retinal rivalry.”

.

.

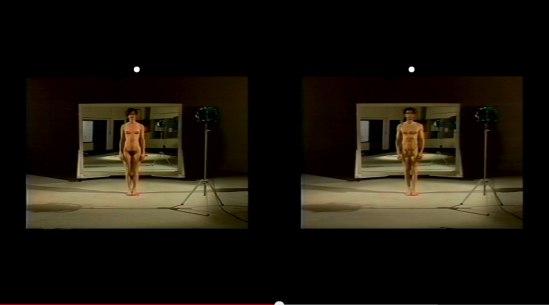

The image above is a frame capture from a stereoscopic video installation that John Hawk created in 1991. The piece is viewed on a elegantly simple version of a Wheatstone mirror stereoscope employing two CRT video monitors. The left and right eye videos were recorded sequentially in a video studio set up with a dance mirror and light stand to provide relative depth cues. A recording of a nude male is shown on one monitor while a recording of a nude female is shown on the other. Binocular rivalry causes the spectator to see an androgynous figure based on an alternating perceptual awareness that occurs over time as the stimuli for the left and right eye compete for perceptual dominance. At points in the video the man and woman walk into and out of frame thus creating another form of binocular rivalry and revealing the sources of the androgynous central figure.

.

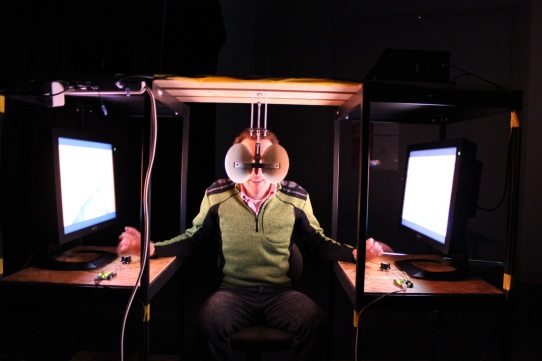

As in John Hawk’s work with binocular rivalry shown in the previous post, Will Hall has employed a video version of the Wheatstone stereoscope to exploit the effect of binocular rivalry with two similar but varied video recordings. Aside from the differences in original video content, a major distinction with Hall’s work is that the spectator is given controls for adjusting the playback speed and temporal direction of the left and right videos. While the fused perception of the stereoscopic view of the static elements recorded with stationary left and right cameras remains constant, the movements of dynamic elements in the videos change over time under the control of the spectator. This results in the classic binocular rivalry effect of a shifting in and out of perception of the moving elements in the scene. In addition to exhibiting and writing about his work, Hall has generously provided instructions to assist people in reproducing and directly experiencing variants of his work by constructing their own diplopiascope.

.

.